From its utilitarian roots in the 19th century, the tourbillon has evolved in the modern era to become the ultimate expression of watchmakers’ technical prowess and avant-garde creativity. We trace its fascinating two-century-plus evolution in this feature from the WatchTime archives.

Throughout the centuries-long history of timekeeping, mechanisms originally developed for entirely practical purposes have been rediscovered and repurposed by contemporary watchmaking visionaries into elements of luxury, much of their charm derived from their seeming obsolescence. Consider the example of the tourbillon, patented 220 years ago by its inventor as a regulating device, which now, in the 21st century, stands as a showcase feature in many of the world’s most coveted timepieces.

The Beginnings

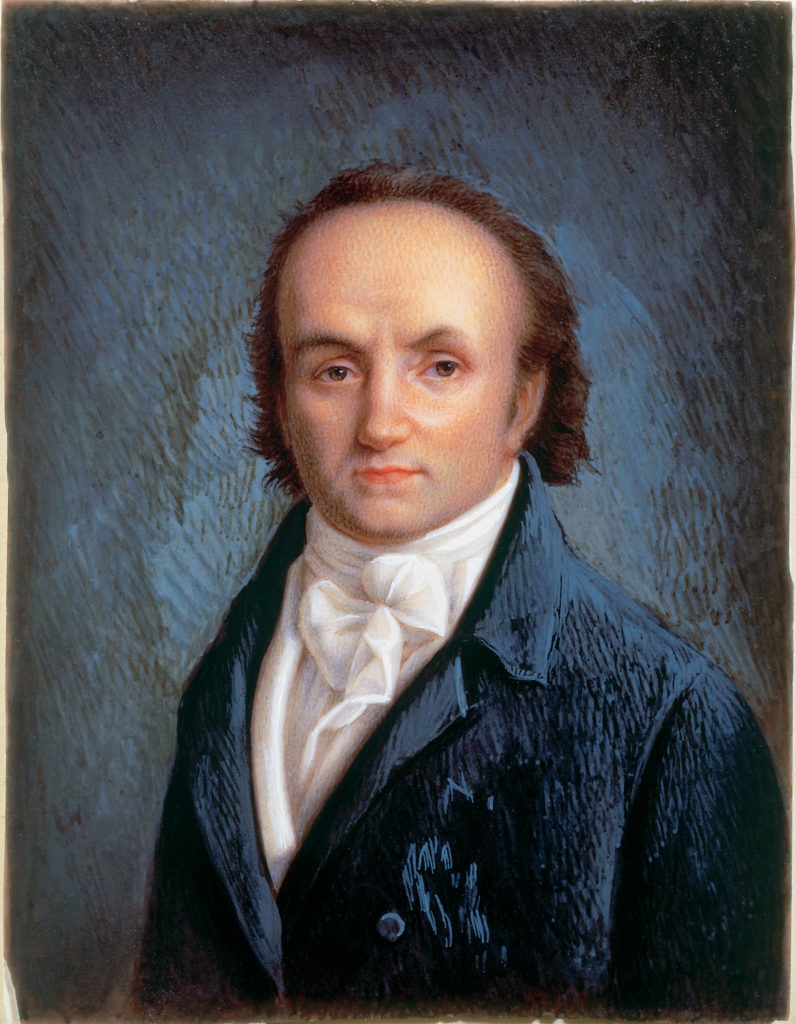

Few pioneers have been as influential in the history of horology as Abraham-Louis Breguet (1747-1823), who counted among his numerous inventions the Perpetuelle, one of the earliest self-winding watches; the tactile watch, which could be read by the touch of fingertips; the so-called Sympathique clock, designed to reset and synchronize watches placed on top of it; and one of the first constant-force escapements. From the atelier he set up in Paris’ Ìle de la Cité in 1775, Breguet plied his trade for a roster of clients that included King Louis XVI and Queen-Marie-Antoinette, before fleeing to Switzerland in the wake of the French Revolution in 1795. It was during this Swiss sabbatical period, between 1793 and 1795, that Breguet likely conceived the idea for his “tourbillon regulator,” naming it after a French word that in contemporary parlance referred to a planetary system rotating on an axis but in modern vernacular is more directly translated to “whirlwind.”

Breguet, who had a foundational background in mathematics and physics as well as watchmaking, understood that gravity had an adverse effect over time on the rate regularity of a pocketwatch’s movement. His solution was to assemble the devices in the movement devoted to regulation and energy transfer — the balance and escapement — into a mobile cage that rotates 360 degrees on its own axis, ideally once per minute, this constant rotation compensating for gravitational pull and thus improving accuracy. “By means of this invention, I have successfully compensated for the anomalies arising from the different positions of centers of gravity caused by the regulator movement,” Breguet wrote in his letter to the French Minister of the Interior to obtain the patent on his invention.

Breguet and his associates would go on to produce around 40 tourbillon watches between 1796 and 1829, for clients ranging from European and Russian monarchs and aristocrats, including George III of England and Ferdinand VII of Spain, to ship owners, sailors and explorers including Sir Thomas Brisbane. The patent, secured in 1801, lasted for only 10 years, thus ensuring that Breguet’s invention would not only outlive him but would continue to be refined and updated by his successors.

Early Upgrades

One of those innovators was Constant Girard (1825-1903), a founder of the modern Girard-Perregaux manufacture, whose most famous contribution to horological history was the Tourbillon with Three Gold Bridges. An admirer of Breguet’s invention who had become known for using it in his own timepieces, Girard was perhaps the first watchmaker who saw the tourbillon’s potential not only as a regulation mechanism but also as an aesthetic asset. At the 1867 Paris Exhibition, Girard presented a gold pocketwatch whose movement was notable for its three parallel bridges with shaped, pointed ends. Girard evolved the design and material of the bridges in subsequent models to establish the distinctive gold, arrow-ended style familiar to fans of the Girard-Perregaux brand today. In 1889, the atelier created the most famous of the Three Gold Bridges pocketwatches, nicknamed La Esmeralda after the boutique in Mexico for which it was made. Pairing an elaborately engraved gold case with a chronometer- accurate tourbillon movement, the watch won a gold medal at that year’s Paris Universal Exhibition and subsequently became the property of Mexican president Porfirio Diaz.

In 1892, a Danish watchmaker named Bahne Bonniksen, who had studied Breguet’s work, developed his own solution to the vexing problem of gravitational interference on a watch’s accuracy. It was similar to the tourbillon in conception but differed in small but significant technical details. Rather than being driven by the fourth wheel, which moves the seconds hand, Bonniksen’s gravity-resistant mechanism uses the third wheel, aka the transmission wheel between those driving the minutes and seconds, to power its rotation. Bonniksen called his invention a karrusel, or carrousel; its construction made it less prone to shocks than a tourbillon and ostensibly less costly to produce. Yet the carrousel never became a popular, mass-produced commodity in the watchmaking world and would remain a historical curiosity until Blancpain resurrected it in the

21st Century for its most exclusive complicated pieces — often combined with a tourbillon or other high complications like a minute repeater.

The next important evolution of the tourbillon sprang from a classroom in Germany. Alfred Helwig (1886-1974), headmaster of the German Watchmaking School Glashütte, sought to improve both the stability and visual impact of the classical tourbillon, whose rotating cage, in Breguet’s design, was anchored between two supporting bridges on the dial side and movement side. Helwig envisioned a tourbillon cage that would instead be cantilevered, or anchored by a single bridge on its bottom side for a more dynamic, unimpeded view into the escapement. The first version of this so-called “flying” tourbillon completed by a group of students under Helwig’s supervision in 1920, was submitted to the German Naval Observatory in Hamburg, where it achieved outstanding results. This style of tourbillon would prove to be popular in the modern era of wristwatches, in which the device completed its journey from practicality to luxury.

Whirlwind To The Wrist

The wristwatch began supplanting the pocketwatch as the timepiece of the masses in the wake of World War I. As a device whose raison d’etre is rooted in counteracting the effect of gravity on pocketwatches, the tourbillon, as one might expect, made its way into wristwatches only in fits and starts across the 20th Century. Timepieces worn on the wrist, of course, are far less susceptible to gravity’s ill effects than timepieces dangling from a chain. Nevertheless, watchmakers continued to be drawn to the technical challenges posed by Breguet’s alluring invention and the prestige of creating a modern version, among them some of the industry’s most historically significant players.

Patek Philippe began producing tourbillon movements for wristwatches as early as the 1940s, most cased in watches designated specifically for Geneva Observatory timing trials of that era. Several of these very rare pieces are now in the Patek Philippe Museum, and perhaps the most famous of them — Caliber No. 861.115, completed in 1945 and designed by master watchmaker André Bornand — caught the eye of Patek Philippe president Philippe Stern, who had it fitted into a modern case to wear as a personal wristwatch circa 1987.

Omega, much better known these days as the maker of the Speedmaster “Moonwatch” chronographs, also dabbled in producing wristwatch tourbillon movements for chronometry competitions in the post-World War II years. The most famous of these is Caliber 301, completed in 1947, of which only 12 examples were ever made. Its tourbillon carriage made a complete revolution every 7.5 minutes, rather than the 60 seconds spelled out in Breguet’s patent application; nevertheless, it achieved a record level of accuracy for a wrist- watch at the Geneva Observatory competition in 1950. Thus far, only one has been found that was actually cased back in 1947 as a prototype; this 37-mm steel watch sold at a Phillips auction in 2017 for nearly $1.5 million.

It was another historical Swiss maison, Audemars Piguet, which gave the world its first self-winding tourbillon wristwatch. Released in 1986, the Ref. 25643, housing the groundbreaking, ultra-thin Caliber 2870, may have also been the first series-produced tourbillon wristwatch, released in a quartz-dominated era in which mechanical watches had become rare and haute horlogerie executions such as the tourbillon were practically non-existent. Caliber 2870’s tourbillon carriage was 7.2 mm in diameter, around 2.5 mm thick, and made of ultra-light titanium, a material then relatively new to watchmaking and never before applied to a tourbillon. The crownless, “hammer” automatic winding system was also unusual, its swinging weight visible at 6 o’clock along with the asymmetrically placed tourbillon aperture at 11 o’clock, at the center of a radiating pattern on the dial. It’s a long-discontinued piece that fans of Audemars Piguet’s Royal Oak models, including those equipped with tourbillons, would scarcely recognize today, but its place in history is assured.

Appropriately, Breguet, the watchmaking maison founded by the tourbillon’s inventor, was one of the earli- est adopters of the tourbillon wristwatch and ultimately one of its leading modern innovators. In 1988, the company, then owned by Investcorp, released a gold-cased timepiece con- taining Caliber 387, a tourbillon movement created by Swiss movement maker Nouvelle Lemania. The watch juxtaposed a classical hours-and-minutes subdial at 12 o’clock with a large tourbillon aperture at 6 o’clock. The Swatch Group acquired both Breguet and Nouvelle Lemania in 1999, folding the latter into the former and renaming it Manufacture Breguet. The model would be a template for many more Breguet tourbillons to come.

Doubling Up

When it became clear that adding a tourbillon to a wristwatch represented both added value and a badge of high-horological bonafides, the race was on to see which manufacturers could develop a timepiece with multiple tourbillons. It was a partnership between an Englishman and a Frenchman that kicked the race into high gear.

Robert Greubel and Stephen Forsey introduced their eponymous brand with a bang at 2004’s Baseworld watch fair, astounding visitors with a type of tourbillon watch that none of them had seen before: it had two tourbillon cages, rotating at two speeds on two separate axes, with the inner cage set at an angle to the outer one. The groundbreaking timepiece, called the Double Tourbillon 30°, established the fledgling Greubel Forsey brand as an independent watch- maker to be reckoned with, and one that would continue to occupy the cutting edge of tourbillon wristwatch technology. To name just a few of its accomplishments, Greubel Forsey’s Tourbillon 24 Secondes model, dropped in 2007, had only a single inclined tourbillon carriage but one that rotated at a super-fast 24 seconds rather than 60; the Quadru- ple Tourbillon à Differentiel, from 2008, as its name implied, included no less than four tourbillons — two double tourbillons to be exact, with the inner two inclined as in the Double Tourbillon. The cages rotate once per minute (inner) and every four minutes (outer); Greubel Forsey added a differential between the two tourbillons to distribute energy between them. Nowadays, multiple tourbillons are mainstays in Greubel Forsey’s collection, often nestled among a host of other elaborate complications and functions.

Genevan maison Roger Dubuis made its own distinctive and indelible mark in the multiple-tourbillon arena as early as 2005, with the introduction of the Excalibur Skeleton Double Tourbillon, whose openworked, in-house move- ment, Caliber RD01SQ, also uses a differential system. Skeletonization and double tourbillons have remained a hallmark of the Roger Dubuis brand, to this day, including in recent motorsport-inspired models designed in collaboration with partners like Pirelli and Lamborghini Squadra Corsa.

Jeweler to the stars Harry Winston joined the party in 2009 with the launch of its Histoire de Tourbillon series, which is devoted to developing avant-garde 21st century iterations on the tourbillon, employing the expertise and bold ideas of today’s most talented watchmakers. For the series’ 10th anniversary in 2019, Harry Winston unveiled the Histoire de Tourbillon 10, jam-packed with four tourbillon regulators, arranged in perfectly symmetrical order at the four corners of the large, rectangular case. All four make a counterclockwise 36-second rotation and are connected by three differentials. The technical idea behind this arrangement is to unify the quartet of regulating mechanisms for an ideal offsetting of the effect of gravity on the movement. Along with two pairs of fast-winding barrels, overlaid, mounted successively, and connected to the tourbillons, this system ensures evenly distributed energy and thus, according to the company, a more precise chronometry.

As one might expect, Breguet also staked out this territory early, albeit in more classically elegant fashion, introducing its Classique Double Tourbillon 5347 in 2006. Its movement features a pair of “orbital” one-minute tourbillons, each driven by its own independent mainspring, linked to a central differential and affixed to a decorated plate that makes a complete rotation every 12 hours, with the central bridge that links the tourbillons serving as the hour hand. In 2020, Breguet released the breathtaking Quai de l’Horloge 5345 version, with a painstakingly openworked architecture and artisanal engravings that pay visual tribute to the Parisian atelier where Abraham-Louis Breguet created many of his masterpieces.

Slimming Down

Audemars Piguet’s ultra-thin tourbillon wristwatch in the 1980s proved to be a forerunner of a slimming-down trend in the haute horlogerie world that began in the late 2000s and continues today.

Piaget, a watchmaker whose stock-in-trade has been making complicated movements as thin as possible since at least 1957, presented its Caliber 600P in 2002. Just 3.5 mm thick, with skeletonized bridges and a flying tourbillon, and barrel-shaped to fit the contours of Piaget’s Emperador case, it was at the time the world’s thinnest tourbillon movement and paved the way for others to follow. Among them were Caliber 1270P, which debuted at SIHH 2011 inside the Emperador Coussin Tourbillon Automatic. The movement combined the flying tourbillon of Caliber 600P with the micro-rotor winding system of another record-setter, Piaget’s automatic Caliber 1208P. As alluded to in the model name, it copped for Piaget the title of world’s thinnest self-winding tourbillon caliber, at 5.5 mm.

For a brief time, Arnold & Son, a prestigious but lesser known haute horlogerie maker named for British watchmaker and Breguet contemporary John Arnold, held the title for thinnest tourbillon watch on the market. Its UTTE (“Ultra Thin Tourbillon Escapement”), launched in 2013, had an 8.3-mm-thin, precious-metal case and held a manually wound caliber, just 2.97 mm thick, that not only incorporated a flying tourbillon but stored a 90-hour power reserve in its two barrels. Just one year later, Breguet introduced its Classique Tourbillon Extra-Thin Automatic 5377 to claw back a distinction that its founder would undoubtedly consider rightfully his: maker of the world’s thinnest tourbillon watch. The gold 42-mm case, with its hallmark fluted sides, was just 7 mm tall, its manufacture Caliber 581DR only 3 mm thick — a smidgen thicker than Arnold & Son’s caliber but equipped with automatic winding via a peripheral platinum rotor.

Breguet held on to the “thinnest automatic tourbillon” title for a little while, but the “thinnest tourbillon overall” record was shattered in short order, by Italian jeweler and watchmaker Bulgari, which introduced its Octo Finissimo Tourbillon in the same year, 2014. At just 1.95 mm, its manually wound caliber is thinner than a Swiss 5-franc coin, and its emblematic octagonal case rises almost imperceptibly above the wrist at 5 mm high. To achieve this milestone, Bulgari’s watchmakers devised a number of technical solutions to reduce the overall thickness of the movement. Its flying tourbillon cage incorporated into its plate, the caliber has two bridges, one for the minute wheel and one for the gear train of the tourbillon cage, and uses ball bearings instead of jewels for many moving parts. Three ball bearings guide and keep in position the barrel, which enabled the length of the spring to be doubled, resulting in an impressive power reserve of nearly 55 hours.

Bulgari continued its assault on the thinness record books in 2018, when its Octo Finissimo Tourbillon Automatic, equipped with the ultra-thin Caliber BVL 288, became the new world’s thinnest self-winding tourbillon. Housed in a sandblasted titanium case, the movement uses a peripheral rotor, made of platinum and aluminum and mounted on ball bearings, two factors that enable it to retain the same wafer-like 1.95 mm silhouette as its manual winding predecessor while also enabling a power reserve of 52 hours. The case dimensions have been reduced even further from those of the 2014 model, to just 3.9 mm thick.

New High-Tech Frontiers

Beyond eye-catching aesthetics and technical bragging rights, however, the tourbillon remains, for some innovative watchmakers, an endless source of challenges and potential improvements.

French master watchmaker Francois-Paul Journe built one of the modern era’s most prestigious and collectible watch brands on the foundation of an avant-garde tourbillon watch he first made as a prototype in 1999. The F.P. Journe Tourbillon Souverain was the first series-produced wrist- watch with both a tourbillon and a remontoir d’egalité, a mechanism originally invented for marine chronometers by John Harrison. The latter device transfers constant force from the mainspring to the escapement, effectively eliminating the problem of a watch’s accuracy diminishing as the main- spring runs down. In 2003, Journe — a disciple of the legendary George Daniels, inventor of the co-axial escapement, and a spiritual heir, some would say, to Abraham-Louis Breguet — updated the Tourbillon Souverain with another horologically complex mechanism from the past, a “dead- beat” or jumping seconds display. For the watch’s and the company’s 20th anniversary in 2019, Journe presented the Tourbillon Souverain Vertical, which added a new vertically inclined positioning for the tourbillon cage, which in this model made its rotation every 30 seconds rather than every minute. While Journe’s obsession with all of his timepieces is chronometry, he also displays a flair for showmanship with the model, surrounding the dial’s tourbillon aperture with a mirrored ring that draws reflected light and admiring attention to the rotating carriage.

In 2008, Germany’s A. Lange & Söhne added the Cabaret Tourbillon to its prestigious lineup of high complications, and as per the Saxon manufacture’s tradition of melding austere elegance with practical functionality, it brought Breguet’s 19th-century device an upgrade both subtle and substantial. The watch housed the first tourbillon movement with a stop-seconds function, manufacture Caliber L042.1. The oscillating balance inside the tourbillon cage can be reset to the precise second by pulling the crown to trigger a complex lever mechanism that pivots a movable V-shaped spring onto the balance wheel rim, stopping the balance instantly. The arresting spring is shaped to ensure the correct amount of pressure on the balance regardless of the cage’s position, and the mechanism preserves the potential energy of the stopped balance spring so that it can restart instantly after the crown is pushed back in. Lange revived the Cabaret Tourbillon in 2021 as a limited edition in its exclusive, artisanal Handwerkskunst collection.

Among the most technically ambitious and visually stunning iterations of the tourbillon are the Gyrotourbillon and Spherotourbillon models produced in limited numbers by Jaeger-LeCoultre. The former, unveiled in 2004, is a tourbillon that rotates on two axes courtesy of its two carriages — the inner one turning once every 24 seconds, the outer once per minute. The point of the two-axis rotation is to improve on the performance of a standard, single-axis tourbillon by keeping the balance moving continuously through a range of positions. For the second-generation Gyrotourbillon 2, JLC increased the speed of the inner cage to one rotation per 18.75 seconds and added a cylindrical balance spring, an element drawn from vintage marine chronometers, to improve the balance’s precision. More technical firsts distinguished the most recent iteration, 2013’s Gyrotourbillon 3, which was the first two-axis flying tourbillon as well as the first wristwatch movement to use a spherical hairspring.

The movement inside 2012’s Duomètre Spherotourbillon also incorporated this type of inclined, bi-axial tourbillon but was redesigned to use fewer components and its tourbillon was sped up again, rotating once every 30 sec- onds while its inclined axis spun around every 15 seconds. A smaller gyrotourbillon — with the inner cage making a super-swift 12.6-second rotation, a new hemispherical balance spring, and a balance wheel in the shape of Jaeger- LeCoultre’s anchor emblem — made its debut in a 75-piece limited edition of the maison’s iconic Reverso model, in that series’ 85th anniversary year of 2016.

Complex Combos

Other world’s-first innovations have emerged from watch- makers combining tourbillons with other impressive technical breakthroughs. Lucerne-based, family-owned Carl F. Bucherer introduced the Manero Tourbillon Double Peripheral in 2019, the first watch that uses peripheral mounting for both its automatic winding rotor and its tourbillon cage. Both the tourbillon cage and the rotor are supported peripherally, the former by three ceramic ball bearings. This construction not only makes for a more stable connection and smoother running, but has the striking visual effect of making the tourbillon appear to be floating inside the watch, with an unhindered view from both above and below.

Vacheron Constantin, which has been innovating in the horological realm continuously since its founding in 1755, unveiled a tourbillon wristwatch with an astounding two-week power reserve in 2012. Its movement, manual-winding Caliber 2260, achieves this 14-day running autonomy with its four barrels, stacked in pairs, interconnected and discharging si-multaneously yet four times more slowly than a single barrel would. The tourbillon carriage is designed to look like Vacheron Costantin’s Maltese cross emblem, each of its rounded tourbillon bars requiring 11 hours of hand craftsmanship. Vacheron eventually installed this exceptional caliber in its most exclusive family, the Collection Excellence Platine, in 2013.

Hublot, a brand known for its forays into unconventional materials and envelope-pushing technology (and which produced a handful of notable tourbillon limited editions in its erstwhile partnership with Ferrari) became the first watchmaker to use sapphire for not only a watch’s case but also the tourbillon bridge of its skeletonized movement, introducing the Big Bang Sapphire Tourbillon in 2018. The Nyon-based maker followed up that innovation two years later with an automatic version, with a 22k gold, dial-side micro-rotor balancing out the one-minute tourbillon cage at 6 o’clock on the skeletonizd face. The movement, Caliber MHUB6035, includes even more sapphire bridges than its predecessor, and is ensconced inside a similarly eye-catching case made of orange sapphire.

After bi-axial tourbillons came, inevitably, tri-axial tourbillons, which were designed to counter gravity in nearly any position a wristwatch would find itself in. The first, called Revolution 3, came in 2004 from one of the early 21st Century’s hottest indie watchmakers, Franck Muller. Girard-Perregaux, historical creator of the Three Gold Bridges, continued to flex its tourbillon muscles with the presentation of its own Tri-Axial Tourbillon in 2014. In 2020, perhaps the most visually arresting example of this style of tourbillon premiered in the playfully named Legacy Machine Thunderdome from MB&F, the brainchild of brand founder Max Büsser and renowned watchmakers Eric Coudray and Kari Voutilainen. Its TriAx tourbillon mechanism, designed by Coudray, replaces the traditional system for multiple-axis tourbillons — which links one tourbillon cage with each rotating axis — with a three-axis, two-cage configuration along with a so-called Potter escapement with a fixed wheel that allows for higher rotational speed for all three cages. The revolutionary mechanism allows for maximum visibility of the tourbillon escapement’s beating heart, on full dis- play under a large, domed sapphire crystal that gives the model its cinematic, sci-fi nickname. Voutilainen’s decorative genius is evident in the dial’s circular guilloché motif as well as on the signature finishing style applied to the ratchet wheels.

Invented by the Swiss and adapted into new and fascinating forms by Germans, Danes, Brits, Frenchmen, and even Americans — RGM founder Roland G. Murphy built the first USA-made, serially produced tourbillon wristwatch, the Caliber MM2 Pennsylvania Tourbillon, in 2010 — the tourbillon continues to exert its hold over watchmaking innovators across the world, including, recently, Japan. After testing the waters with the Credor Fugaku Tourbillon in 2016, Grand Seiko presented in its 60th anniversary year of 2020 a new in-house movement with an entirely new type of constant-force escapement. The T0 (T-zero) concept caliber, not yet installed in a case, takes a novel turn on the trail blazed by F.P. Journe, placing the tourbillon, with its blued titanium cage, and the remontoire d’égalité on a single axis and using a manufacturing process called MEMS (Micro Electro Mechanical Systems, used to make semiconductors) to form gears with teeth whose precision is measured in microns.

As the tourbillon continues to make its presence felt throughout the global watch industry, it appears unlikely that this 19th century invention will be returning to the vault of historical curiosities anytime soon.

A version of this article first appeared in the September-October 2021 issue of WatchTime.

I have the the Girard Perregaux trois ponts d’or Esmeralda like piece in rosé gold; the Omega Tourbillon Central #10 (the transition piece) in pink gold; the automatic Audemars Piguet marvel piece in yellow gold, which I call Akhenaton; the Breguet 387 Tourbillon in yellow gold; the F.P.Journe Souverain in red gold; the Vacheron Constantin Tourbillon 2000 in yellow gold; and the original Ulysse Nardin Freak in pink gold which, if not one of the tourbillons, is a rarity as excentric.

Humberto Pacheco