Blancpain’s Villeret collection channels the haute horlogerie roots of the world’s oldest watchmaking brand and continues to innovate with an array of grand and practical complications. We explore the collection’s origins, as well as its historical and modern highlights, in this feature from the WatchTime archives.

The author Thomas Wolfe is often credited with coining the idiom, “You can’t go home again,” though Wolfe himself is believed to have taken it from a conversation with his friend, British-Australian journalist Ella Winter, and asked her permission to use it for the title of his 1940 novel. It’s likely, however, that both writers would have thought twice if they’d seen what Blancpain, one of the Swiss watch world’s oldest and most accomplished manufactures, has accomplished by returning to the earliest years of its history, which started in the picturesque town of Villeret.

Blancpain, today one of the Swatch Group’s triumvirate of Swiss “prestige” brands alongside Breguet and Jaquet Droz, was founded in 1735 in Villeret, in the Bernese Jura, but has been based in the town of Le Brassus in the Vallée de Joux since 1983. It’s fair to say that it has become known in the modern watch-enthusiast community more for its pioneering divers’ watch, the Fifty Fathoms, than for its high-complication prowess and historically elegant designs. Nevertheless, Blancpain’s commitment to classical watchmaking has never wavered, and it is within the nostalgically named Villeret collection that the brand has established many of its haute horlogerie milestones.

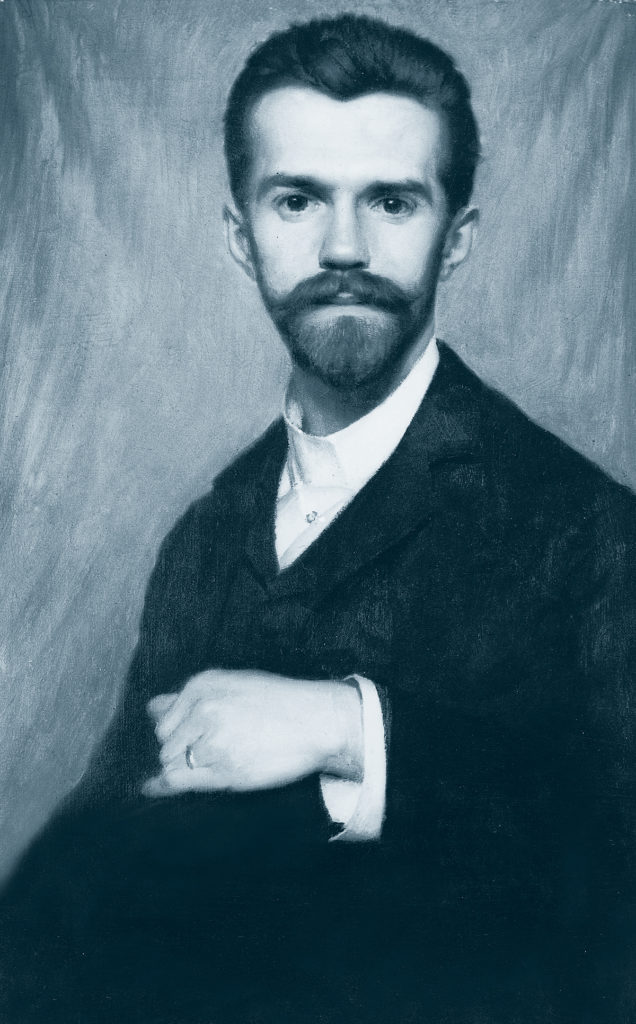

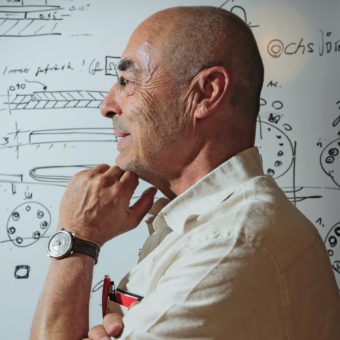

“Villeret is the place where Blancpain was born,” states Marc A. Hayek, President and CEO of Blancpain (as well as Breguet and Jaquet Droz). “The village is part of our identity, but also represents the starting point of watchmaking history. In the early 18th century, it was inhabited by inventive and hard-working farmers imbued with a profound taste for fine mechanisms and good workmanship. One of them was Jehan-Jacques Blancpain, who registered himself as a watchmaker in the village records in 1735, founding what would become the world’s oldest watchmaking brand.” The watch firm that Jehan-Jacques Blancpain set up in his farmhouse would remain family-owned until 1932, when Frédéric-Emile Blancpain passed away, and the company was subsequently renamed by its new owners “Rayville,” a phonetic anagram of “Villeret,” as was required by Swiss law at the time. Another ownership change, in 1983, brought back the original company’s name but moved its manufacturing, after more than two centuries, from Villeret to Le Brassus. In 1992, Blancpain was purchased by the SSIH, later to become the Swatch Group.

The roots of the Villeret collection reach all the way back to what most would consider the dawn of Blancpain’s modern era, in its early days in Le Brassus, when the brand defiantly sailed into the headwinds of the Quartz Crisis by doubling down on traditional mechanical complications, many of which had virtually disappeared from the market. In 1983, Blancpain released its now-iconic Caliber 6395, combining a so-called “complete calendar” with a moon-phase indication. The watch, with weekday and month in separate windows, a dedicated date hand with accompanying peripheral scale, and a “mischievous” moon with playfully illustrated face, also established many of the aesthetic codes by which we recognize Villeret models today: applied Roman hour numerals, a double-stepped bezel and elegantly shaped hands reminiscent of sage leaves. Historically, it was the smallest complete calendar moon-phase movement plate ever made. “This piece was more than a tribute to watchmaking tradition,” Hayek emphasizes. “It also broke new design ground and led the way for the entire watchmaking industry to follow, reintroducing complications and interest in mechanical watches.”

That revival of interest continued when another largely dormant horological complication, the minute repeater, took center stage in 1987’s Caliber 35. In those days before the renaissance of the mechanical watch, creating such a mechanism, especially in a wristwatch, was bold and difficult enough, but Blancpain also made it another record-setter: it was the world’s smallest minute repeater in both diameter (23.9 mm) and total volume (4.85 mm thick); moreover, it featured automatic winding and hand-finished components, some thinner than a human hair. A few years later, in 1989, Blancpain achieved another milestone, becoming the first watchmaker to equip a wristwatch with a flying tourbillon — a device in which the rotating cage encasing the watch’s balance-wheel assembly (invented originally to combat the effects of gravity on pocketwatch movements) is supported from a single bridge underneath rather than suspended between the traditional two bridges. This design helps ensure an unobstructed view of the tourbillon from the open dial and required the invention of a minuscule ball bearing assembly. The Blancpain Caliber 23 that pioneered this mechanism was also at the time the world’s thinnest tourbillon movement and, as if that weren’t enough for posterity, also inaugurated another feature we now associate with Blancpain’s highest-echelon movements: an astonishing eight-day power reserve stored in three serially arranged barrels.

Blancpain reached even higher with the simply dubbed 1735 timepiece in 1991. At the time the world’s most complicated, series-produced, automatic wristwatch, its 740-piece movement powered a minute repeater, tourbillon, perpetual calendar, moon-phase, and split-seconds chronograph. Each model required a full year to make, which could explain why Blancpain produced only 30 pieces total of the 1735.

In 2004, practicality, rather than pushing watchmaking boundaries, inspired another invention that now defines Villeret timepieces, particularly its perpetual calendars. One of Blancpain’s watchmakers, whose identity is apparently lost to history, took note of the correctors on the sides of a perpetual calendar watch — the inset buttons, usually pushed with a thin-tipped tool, that facilitate quick adjustments to the calendar functions but nevertheless detract from the case’s smooth, harmonious lines. The watchmaker wondered aloud whether these correctors could be moved to an area on the case where they would not be visible. Blancpain’s innovative answer was to install the correctors — which activate levers built into the movement to change the date, day, month, and moon-phase — under the lugs, making them easily accessible but hidden from view while the watch is worn. Better yet, these under-lug correctors, which are now patented, can be activated with just a finger push rather than an outside tool. These subtle but ingenious devices are standard on Villeret timepieces today.

Here in the second decade of the 21st century, much of the luxury watchmaking world has caught up with the revival of traditional mechanical complications that Blancpain was so boldly pioneering in the 1980s. However, the Villeret collection continues to be fertile ground in which to flex horological muscles, on either a small, practical scale or a grander one. In 2011, Blancpain’s Caliber 5235DF, debuting in the Villeret 8 Days Half Timezone model, addressed a concern of world travelers — melding its now-famous eight-day power reserve to a mechanism that could set a second time zone in 30-minute increments rather than the standard 60-minute GMT settings — enabling accurate readings of local times in places like India, Southern Australia, and Newfoundland.

Blancpain also offers more traditional GMT functions within the Villeret family, often in clever and practical combinations with other mechanisms. In 2002, the maison released its first Quantième Complet GMT model, combining the dual-time indicator with its “complete calendar,” defined as a watch that displays the day, date, and month in addition to the time, with a moon-phase as an optional addition. Blancpain’s distinctive take on this style of timepiece has become a cornerstone of the Villeret collection: its day of the week and month are in adjacent windows below 12 o’clock, its date indication comes by way of a serpentine hand on a numbered scale on the dial’s rim, and Blancpain’s hallmark “mischievous” moon smiles out at the wearer in its aperture at 6 o’clock. Unlike an annual calendar or perpetual calendar, the simpler “complete” calendar requires more frequent attention to keep it accurate: the wearer must manually advance the date in months of less than 31 days. The model’s complexity is taken up a notch with the addition of a red-tipped pointer hand indicating a second time zone on a 1-to-24 scale inside the ring of applied Roman numerals.

In 2012, the Villeret collection, already populated with all types of calendar timepieces, once again expanded its horizons — and spoke to a growing audience — with the debut of its Traditional Chinese Calendar. “Blancpain is one of the brands with the longest historical presence in China,” says Hayek. “We have always been deeply interested in its exceptionally rich culture. We wanted to honor this age-old culture by introducing a useful yet symbolic model combining the fundamental principles of a lunisolar calendar with the date according to the Gregorian calendar. Given that the basic unit of these two time division systems is not the same, this represented a real technical complexity.”

Like Blancpain’s other calendar watches, it has a date function with a serpentine hand and a moon-phase indicator in a subdial at 6 o’clock. Its other calendar displays, on subdials at 12, 3 and 9 o’clock and an aperture at 12 o’clock, are all keyed to the millenia-old, traditional Chinese calendar, which differs from the modern Gregorian calendar in several significant ways. The Gregorian calendar uses the solar day as the base unit of measuring time, while the Chinese calendar is a solar calendar that uses the lunar cycle, which comprises precisely 29.53059 solar days, as its base unit. A year made up of 12 lunar months would be 354.36707 days in length, about 11 days too short in comparison with our familiar solar year of 365.242374 days. This means that an entire leap month of either 29 or 30 days is sometimes necessary to preserve the calendar’s symmetry with the cycle of the seasons. In essence, a year with a leap month (13 lunar months) is longer than a traditional solar year and a year without one (12 lunar months) is shorter. This is why the date of the Chinese New Year varies from year to year.

The watch also incorporates cosmic and mythological elements like the 12 signs of the zodiac, represented by 12 animals; the five elements; and the so-called 10 celestial or heavenly stems. Also, each day is divided into 12, rather than 24 units (also corresponding with the 12 zodiac animals), mean-ing that one Chinese hour is equivalent to two of ours.

All of these elements are recorded and displayed on the grand feu enamel dial of Blancpain’s watch. The subdial at 12 o’clock indicates the double-hours and their symbols, while the window above it shows the zodiac sign of the current year. The subdial at 3 o’clock, with a yin-yang symbol at its center, depicts the symbols for the five elements and the celestial stems, and the one at 9 o’clock indicates the traditional Chinese month, date, and leap month. Blancpain’s newest edition for 2020, The Year of the Rat, features the eponymous rodent at 12 o’clock on the dial as well as engraved on the white-gold rotor that powers the self-winding Caliber 3638. Cased in platinum, it’s limited to 50 pieces.

In today’s watch arena, thinness, in both movements and cases, is increasingly associated with elegance, and the Villeret “Ultraplate” addresses the growing appetite for slender yet meticulously engineered timepieces. Launched in 2019 and cased in platinum, the original 40-mm, boutique-exclusive Villeret Ultraplate (“ultra-thin” in French) is a time-only model powered by the manual-winding Caliber 11A4B, based (as are many of the modern Villeret calibers) on Blancpain’s Caliber 1150. Despite its wafer-like profile (just under 3 mm thick, inside a case just 7.4 mm thick), its two series-coupled barrels store an impressive 100-hour power reserve while guaranteeing a constant flow of energy. Its silicon balance spring ensures lower density, increased shock resistance, and imperviousness to magnetic fields — all factors that increase chronometric performance. On one of its large, côtes de Genève-enhanced bridges, the movement has an indicator for the power reserve, via a blued hand on a semicircular scale.

In 2020, Blancpain added another Ultraplate model, bearing the same midnight-blue dial of its platinum predecessor but in a slightly thicker 18k rose-gold case, at 8.7 mm. Necessitating the smidgen of additional space was the automatic movement, the 1150-based Caliber 1151, and its engraved gold rotor with honeycomb motif. The movement, displayed behind a sapphire caseback, offers the same silicon-equipped chronometric technology and four-day-plus power reserve of its manually wound sibling.

Also attired in blue, and occupying the higher end of complexity, is 2019’s Villeret Quantième Perpétuel 6656, in a 40-mm platinum case and limited to 88 boutique-exclusive pieces. Powered by the self-winding manufacture Caliber 5954, with a solid gold rotor and silicon hairspring, the watch’s attractive sunray blue dial features the classical, elegantly symmetrical look of Villeret perpetual calendars, with subdials at 3, 9 and 12 o’clock, the anthropomorphic moon-phase display at 6 o’clock, and a central seconds hand gliding above the white gold Roman numerals, its counterweight bearing the stylized “JB” motif of Jehan-Jacques Blancpain. The user-friendly under-lug correctors offer easy setting and resetting of the watch’s array of functions, making it unique even in the exclusive world of perpetual calendar wristwatches.

If the calendars and GMT pieces are the thoroughbred workhorses of the Villeret collection, the minute repeaters, carrousels, and tourbillons are the show horses. And in true Villeret fashion, those pieces can also offer heretofore unseen blends of horological functions. The Villeret Tourbillon Volant Heure Sautante Minute Rétrograde, unveiled in 2018, is a reinterpretation of the groundbreaking flying tourbillon wristwatch the brand released in 1989, made even more complex by the addition of two complications used for the very first time in the collection. In the model, whose 42-mm case is in either rose gold or platinum (the latter limited to 50 pieces), Blancpain has removed the lower bridge of the flying tourbillon — which already lacked the obstruction of an upper bridge — replacing it with a clear sapphire disk. The visual effect makes it appear as though the balance wheel and escapement inside the tourbillon cage are floating in space. As if this were not revolutionary enough, Blancpain also added, for the first time in any of its models, both a jumping hour and a retrograde minutes display. The round, gold-rimmed window indicating the digital hour numerals has been placed inside the minutes subdial, under the tourbillon aperture, to complete the look of the classical grand feu enamel dial, crafted using the traditional champlevé technique. Powering the watch, and on display through a sapphire caseback, is an in-house movement with hand-guillochéd bridges and a guillochéd disk that serves as an indicator for the lengthy six-day power reserve.

Hayek cites the Villeret Équation du Temps Marchante, with its co-axial minute hands to indicate mean and real solar time, and the Caroussel Minute Repeater Flyback Chronograph, with its innovative system of cathedral gongs fixed to the inside of the case, as other examples of pioneering haut- de-gamme pieces within the Villeret collection — demonstrating the breadth of notable complications, and combinations of complications, the series continues to offer. “For nearly four decades, the village of Villeret has been lending its name to our most classic collection,” says Hayek, “which reflects the soul of generations of talented men and women who contributed to the establishment and development of the art of watchmaking.” With the Villeret collection, Blancpain has not only shown that a watch manufacturer can, in fact, “go home again,” at least in spirit; it can continue to build on that home’s strong and lasting foundations.

Great read. Now I am more than ever inclined to own a Blancpain!

Surprising that you did not mention the 1180 movement developed in the 1980’s and used in the Villaret range Thinnest self winding chronograph movement for some 25 years; first Swiss use of a vertical clutch in an elegant design that was copied by other manufacturers; a movement that has also been used by Audemars Piguet and Vacherin Constantine amongst others. The movement was developed under the direction of M. Edmund Capt (who was also the design engineer of the Valjoux 7750.

Great article! I really enjoyed the walk through the different Villeret models over years. One question that popped in my mind while reading the article: is Blancpain producing the calibers used in Villeret watches?