In 1969, the consortium of Heuer-Leonidas, Breitling, Buren-Hamilton and Dubois Dépraz vied with lone wolves Zenith and Seiko in the race to launch the world’s first automatic chronograph movement. How did these brands keep their developments secret? And how did the watch world change? In this feature from the WatchTime Archives, we searched the past for clues.

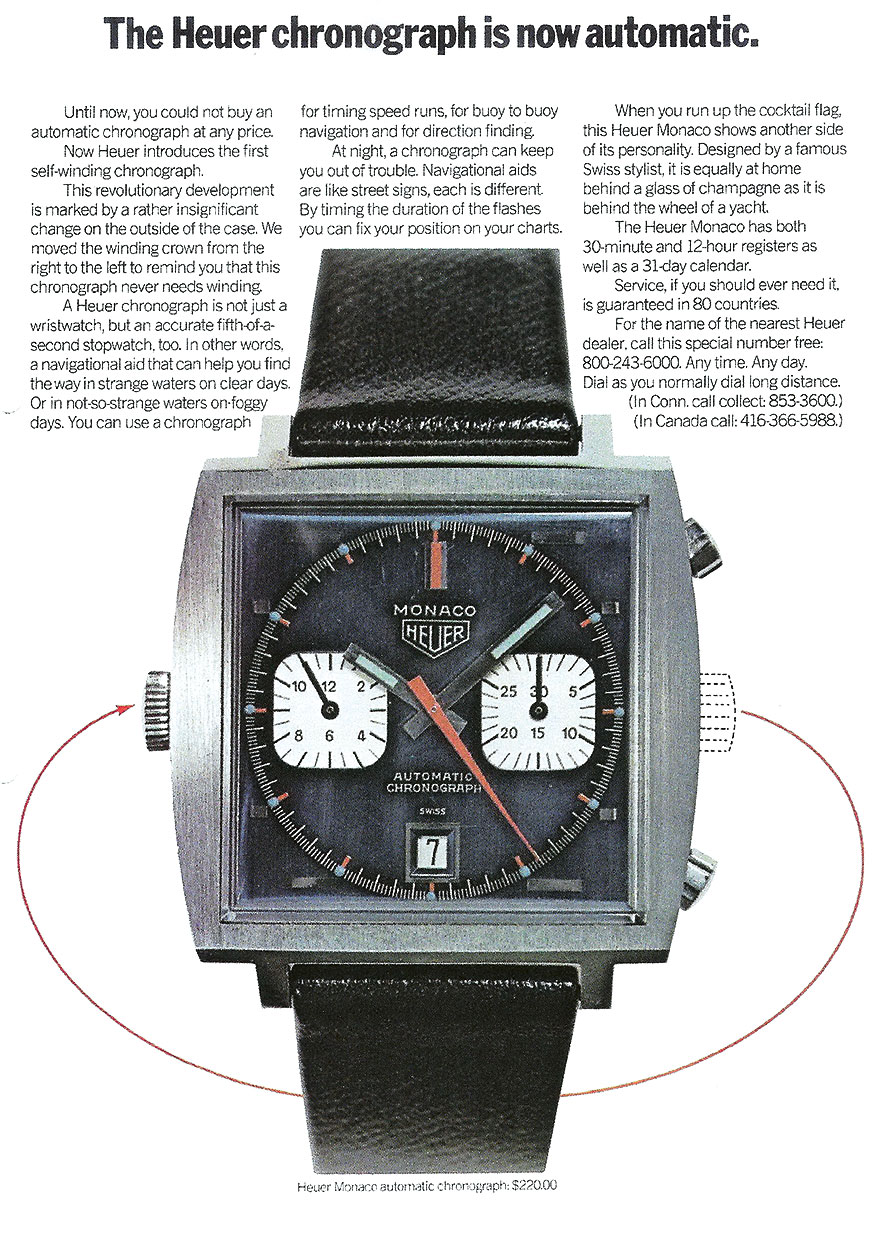

While reading his daily newspaper on the morning of Jan. 10, 1969, Jack Heuer, general director of the Heuer watch brand, suffered such a shock that he almost dropped his coffee cup. A short article announced that Heuer’s competitor Zenith had developed the world’s first automatic chronograph and was already showing functional prototypes of El Primero. How could this be true? Jack Heuer’s company was part of a consortium that had been working on this very same task under tremendous time pressure and the strictest secrecy for the past three years. The launch of Caliber 11 was scheduled for March 3. How could Zenith have beaten them to the punch?

This story is one of the most fascinating narratives in the history of the modern watch industry. It took place in a year that, like the entire previous decade, was characterized by technical progress and profound social change, including the first manned landing on the moon, the maiden flight of the Boeing 747 jet and the flower power movement. The whole decade was supercharged by the economic boom, especially in the automotive industry, and by spectacular auto races, whose champions thrilled large crowds. The zeitgeist of new mobility and communication was omnipresent. The world was ticking to a steadily accelerating rhythm: more and more powerful cars rolled off the assembly lines and more and more people could afford to buy them.

The Swiss watch industry, which cultivated centuries-old traditions, tried to keep pace with the innovation of this new era: they knew that their industry had no choice but to renew itself if it hoped to keep up with the faster pace of the times, particularly with the looming specter of competition from the Far East. In retrospect, we can see that the Quartz Crisis, which would jeopardize the very survival of Switzerland’s watchmaking industry a decade later, had already begun to cast its shadow toward the West. Faultfinders would later claim that technological progress had caught the Swiss napping. Developing a modern automatic chronograph became a kind of Holy Grail for big-name manufacturers in the elite world of short time measurement.

Considering the wide selection of self-winding chronographs available today, it’s difficult to imagine how great a challenge this threefold problem posed. Never before had anyone succeeded in coaxing the practicality of an automatic winding system and the popular functionality of a chronograph into the narrow confines of a wristwatch’s case.

Gerd-Rüdiger Lang, who was employed by Heuer at the time and would later found the Chronoswiss brand, recalls the situation. “The automatic chronograph was the greatest horological invention of the 20th century, which had otherwise produced nothing genuinely groundbreaking in this field. Switzerland’s chronograph manufacturers hoped it would give them access to new markets and serve them as an innovative and sales-boosting bestseller – if they could launch it before Omega, which led the chronograph market at the time.”

A Complex Construction

Chronograph fans had no choice but to wear hand-wound models because the thorny technical dilemma of a self-winding “time writer” remained unresolved. The first hurdle was to overcome the energy problem. When a chronograph is switched on, its seconds hand and its counters for the elapsing minutes and hours consume much more energy than a classic time display, so they demand much greater performance from the self-winding mechanism. Watchmakers also had to leap a high bar by devising a design that would intelligently combine the two complex mechanisms, deploy the various additional components (especially the rotor) in an optimally space-saving arrangement, and provide the necessary “passageways” to accommodate the numerous drive shafts. All of this, it should not be forgotten, had to be accomplished within the diminutive volume of a wristwatch’s case. These ambitious goals occupied the brightest minds at R&D departments in the 1960s, where they pursued their quest for solutions while preserving the utmost secrecy.

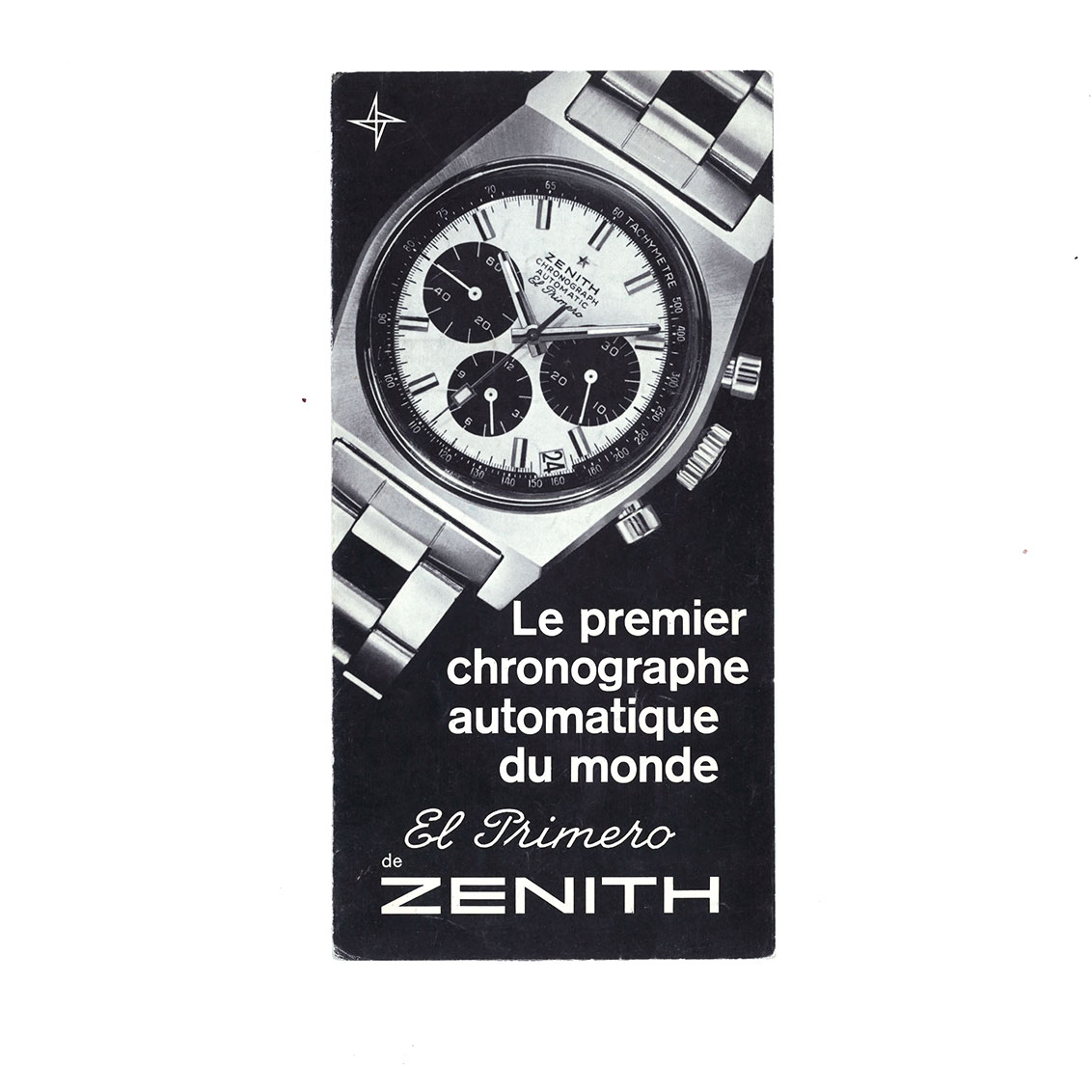

We now know that the first company to begin developing a self-winding chronograph wristwatch was Zenith, which started the project in 1962 and planned to launch the world’s first automatic chronograph to coincide with the company’s centennial in 1965. But this ambitiously early date could not be kept: four more years would come and go before the project could be completed and the first prototype could be made available.

A Coalition of Competitors

Project 99 was the code name under which some of the most important specialists in short-term measurement joined together: Breitling, Heuer-Leonidas and Hamilton-Buren. The establishment of this illustrious circle was preceded by a request from a highly specialized movement designer and true specialist of his era, Gérald Dubois, who directed the technical department at Dépraz & Cie. Founded in 1901 and based at Le Lieu in the Vallée de Joux, this company ranked among the biggest suppliers of chronographs and owed its reputation to numerous developments in the field, including the column-wheel mechanism and the first adjustable module chronograph (Caliber 48), which debuted in 1937. Gérald Dubois was the grandson of the company’s founder and had long been in favor of developing an automatic chronograph, but its realization required an investment that was too large for his company to finance on its own.

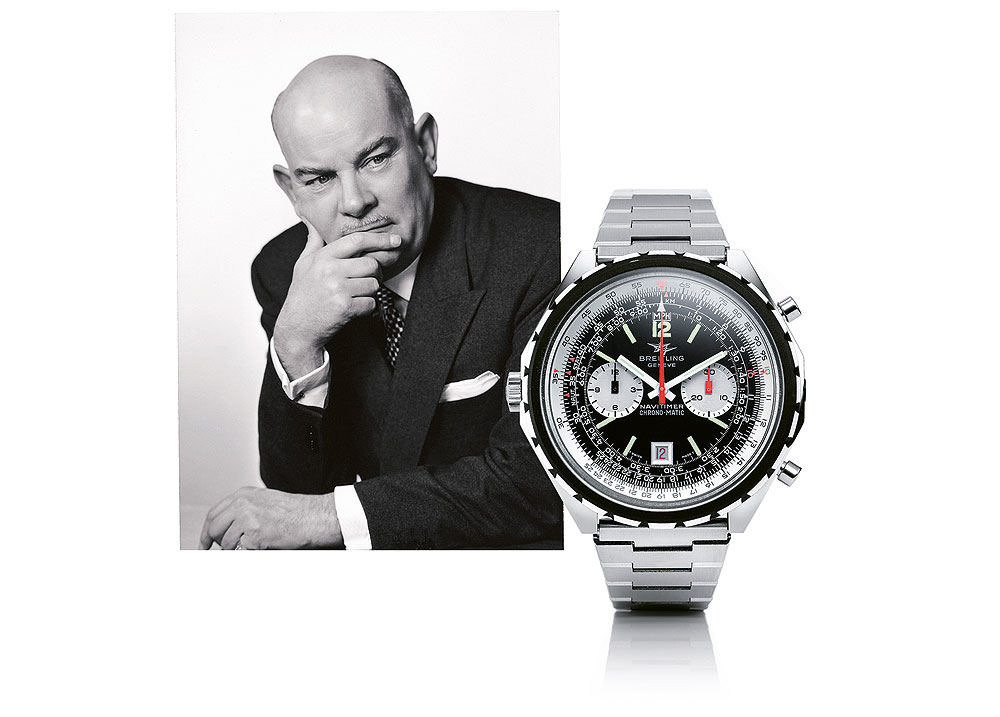

Gérald Dubois contacted Willy Breitling in 1965. Breitling, who was head of the Grenchen-based watch brand, was immediately enthusiastic about the project. The duo asked Jack Heuer, general director of Heuer-Leonidas, to join them. Heuer agreed because he shared their belief that the future belonged to the automatic chronograph. The fourth member of the group was Buren, the movement manufacturer that was acquired by the American brand Hamilton in 1966. The same year, after the costs had been contractually allocated and the patent rights had been granted, the consortium kicked off the development, which took place in secret. Gerd-Rüdiger Lang, who joined the Heuer company as a watchmaker in 1968, recalls that no one on the staff had the slightest inkling of the secret project.

This coalition of competitors marked the beginning of a unique collaboration among rival brands and suppliers. Their alliance bore fruit with the debut of Caliber 11 three years later. Breitling designated this movement as the Chrono-Matic. Heuer’s dials bore the same name, albeit with a slightly different spelling – Chronomatic.

An Unexpected Opponent

But a Japanese giant was not asleep. Seiko, which had been in the premium segment with its Grand Seiko models since the early 1960s and now competed with Swiss manufacturers, also began a similar development in the mid-1960s. Seiko’s secret project was code named 6139. A year earlier, when the world was watching the Olympic Games in Tokyo, Seiko had presented its first chronograph wristwatch, which still relied on manual winding. Meanwhile, the brand had also begun developing a totally different technology: quartz. But that, as they say, is another story.

Three Different Technical Approaches

All three competitors were striving to achieve the same goal, but each pursued its own technical approach. The magic number 36,000 came into play at Zenith. This figure needs no explanation among chronograph enthusiasts, who are well aware that it specifies the number of semi-oscillations completed per hour by the balance in automatic caliber El Primero. Its fast-paced balance vibrated at the previously unattainably speedy frequency of 10 beats per second, which enabled this automatic chronograph movement to accomplish the unprecedented feat of measuring elapsed time to the nearest 1/10th of a second. Another distinctive feature of this technology was the integrated architecture of the chronograph mechanism. El Primero was a self-contained ensemble with a ball-borne central rotor and a column wheel instead of a cam. An especially clever detail was that the movement needed neither a module nor an additional mechanism. And notwithstanding its high frequency, El Primero offered a remarkably long 50-hour power reserve and had been miniaturized so its innovative technology could fit into a space measuring just 6.5 mm by 29.33 mm. Each characteristic was a success and the entire ensemble was nothing short of spectacular. Moreover, El Primero was also aesthetically pleasing: the harmony embodied by the original construction, which still distinguishes El Primero calibers today, has raised the pulse rates of generations of chronograph fans.

Many large watch manufacturers subsequently equipped their chronograph wristwatches with Zenith’s trailblazing masterpiece. Probably the best-known example is the Cosmograph Daytona: Rolex began encasing a modified version in its chronographs in 1987. This transformed the Daytona into a self-winding chronograph. The Daytona continued to encase Zenith’s movement until the year 2000, albeit with a reduced oscillating frequency of only 28,800 hourly vibrations and a balance wheel equipped with Microstella adjusting screws. Other brands, including Bulgari, Daniel Roth and Ebel, also relied on El Primero. Ebel launched a perpetual calendar wristwatch based on Zenith’s movement in 1989.

A Modular Construction with a Micro-rotor

In contrast to Zenith’s integrated architecture, the Project 99 consortium pursued an approach based on a modular concept similar to one used in early pocketwatches with complications. The chronograph mechanism was mounted on a plate in Caliber 11 (the Chrono-Matic) with oscillating pinion coupling. Three screws affixed this independent unit to the bridge side of the movement. The oscillating pinion coupled the chronograph to the gear train. To provide sufficient space, the team abandoned the concept of a central winding rotor positioned above the movement and opted instead for a “planetary rotor,” which Buren had developed under the leadership of technical director Hans Kocher in 1954. One consequence of the movement’s architecture with its integrated micro-rotor was that the crown had to be positioned on the left side of the case. This feature was later marketed using the slogan: “The chronograph that doesn’t need winding.” Simpler assembly and maintenance were the perceived advantages of the sandwich-style construction as “an independent frame that can be easily removed and replaced.” As at Heuer, this covert project was declared classified at Breitling. Everything related to the development of Caliber 11 was discussed in encrypted form during clandestine meetings in back rooms. Only a few confidants of watchmaker Marcel Robert and Willy Breitling were privy to the confidential endeavor.

Seiko chose a third path. The brand had secretly developed a watch that demonstrated Seiko’s high degree of technical sophistication and would prove its precision three years later when this timepiece with its yellow dial ticked on the wrist of American astronaut William R. Pogue in outer space. The 6139 also relied on an integrated construction with column wheel, central rotor and energy-efficient vertical coupling, as well as the “magic lever,” a specialty that Seiko had used since 1959 to increase the efficiency of the winding mechanism. Mounted directly on the rotor shaft, the magic lever tapped all the energy of the oscillating weight, regardless of the rotor’s direction of rotation. A date display and a day-of-the-week indicator with quick correction were also installed.

The Tension Mounts

Let’s go back to Jan. 10, 1969, the date on which Zenith’s press release announced, “The merit of this outstanding creation makes the entire Swiss watch industry shine on the world’s major markets, where the competition is growing increasingly fierce.” Jack Heuer called a breakfast meeting to decide how to proceed. The partners agreed to stick with their plan of simultaneous press conferences in Geneva and New York on March 3, 1969. In the presence of Heuer, Willy Breitling and Hans Kocher, the Caliber 11 Chrono-Matic was presented with great ceremony to the world’s journalists. Judging by their enthusiastic response, the reporters apparently weren’t bothered by the fact that the consortium had crossed the finish line nearly two months after its arch rival. Gérald F. Bauer, president of the Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry (FH), opened the event in Geneva at 5 p.m. local time. Praising the technical masterpiece, Bauer highlighted the team spirit that had made it possible to “launch this new high-performance product for the Swiss watch industry.” Heuer had prepared answers to questions about Zenith’s El Primero, but was surprised that the journalists didn’t ask any. The simultaneous press conference in Manhattan, which began at 11 a.m. Eastern Time, was also attended by high-ranking Swiss industry representatives, including the President of the U. S. Foreign Office of the Swiss watch industry and Switzerland’s Consul General in New York. The international edition of the Journal suisse d’horlogerie et de bijouterie dedicated its front page and a 16-page supplement to the event. The magazine’s headline declared: “Three Swiss companies worked behind closed doors and launched a watch that doesn’t really exist: the automatic chronograph.” Willy Breitling emphasized the importance of innovation for the industry in general and especially for the company that his grandfather had founded saying, “Certain stages in the development of a brand are decisive for its future. Today we are witnessing an event of capital importance, and I am sure you realize that it is a source of great joy for us.”

Three Premieres

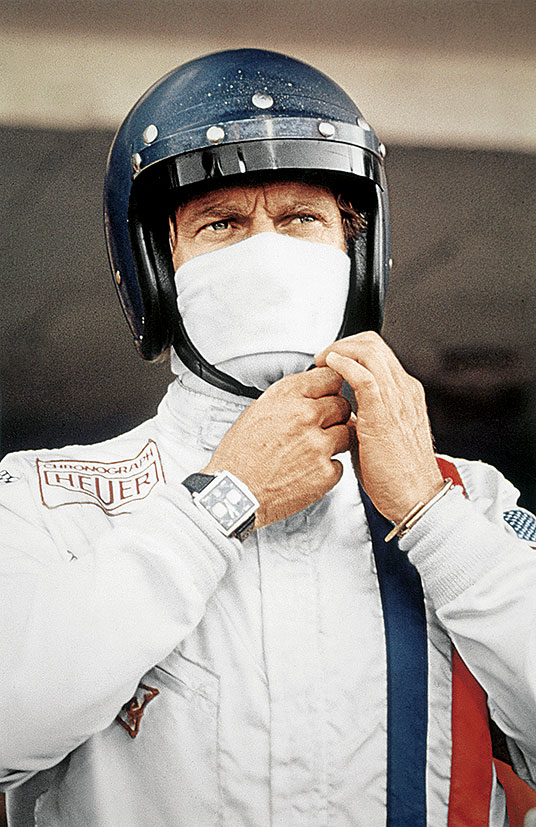

Each member of “Project 99” selected its best-selling watches to encase the Chrono-Matic. Breitling ensconced it in the Navitimer and Chronomat; the first collection also included a cushion-shaped model, a new interpretation of the square chronograph from 1966 and a tonneau with a divers’ bezel. Heuer put Calibre 11 inside the Carrera, the Autavia and the new Monaco. The Monaco blazed new trails not only with its modern self-winding movement but also with the world’s first water-resistant square case. Hamilton launched the elegant Hamilton Chrono-Matic with a legendary “panda” dial, which is available today in a nearly identical look. An unmistakable feature of all these models was the crown on the left side of the case, where it demonstrated that this automatic chronograph no longer needed manual winding.

Silence Is Golden

All brands in the consortium presented the innovation in March 1969 in Basel at the Mustermesse, the “Sample Fair” that would later become Baselworld. Jack Heuer received a compliment from an unexpected source: Shoji Hattori, Seiko’s president, visited Heuer at the stand and congratulated him on his technical breakthrough. Heuer said, “Naturally, I was very flattered. But Mr. Hattori didn’t divulge even the slightest hint that Seiko was showing its 6139 at the fair.” Heuer subsequently expressed his admiration for Seiko’s “rather clever product strategy.” Before the international launch of a new watch, its maker typically tests it first on the domestic market to solve any remaining problems. As in the fable of the tortoise and the hare, Seiko’s apparent slowness ultimately paid off. According to Jack Heuer, the Japanese company brought sales of Heuer’s product almost to a standstill on the U.S. market a few years later, a disappointment that he also attributed to an unfavorable exchange rate. Heuer nevertheless ended the 1969 financial year with record-breaking results: the brand increased sales by 34 percent thanks to the Caliber 11 Chrono-Matic. The original caliber was manufactured until 1970 and afterward further developed into Caliber 12. Heuer continued producing the movement until 1985. The Autavia was the last model to encase Caliber 11. Breitling used it from the end of 1968 to 1978.

The Present

El Primero is the only one of these pioneering movements from 1969 that has been uninterruptedly manufactured from its debut to the present day, except for a brief hiatus during the Quartz Crisis. El Primero received a boost after Zenith was acquired by the LVMH Group in 1999. The high-frequency movement served as the basis for a flurry of new developments. These included additional modules to support diverse displays, as well as modifications with a partially skeletonized base plate so the escapement could be viewed through an aperture in the dial. El Primero Caliber 4021 was introduced with an additional power-reserve display and even with a tourbillon. Caliber 4031 combined a minute repeater with chronograph, alarm and second time zone. El Primero Stratos Flyback Striking 10th kept time during an extraordinary adventure on Oct. 14, 2012, when Felix Baumgartner jumped from the stratospheric altitude of 39 kilometers with this watch strapped to his wrist. His plunge made him the first human being to outpace the speed of sound. Baumgartner and his timepiece survived the acceleration, altitude, pressure and temperature differences unscathed. The watch worked just as well after landing as it did on take off.

Half a century after its premiere, El Primero remains the world’s most accurate serially manufactured chronograph thanks to its ability to measure brief intervals to the nearest 1/10th of a second. It also has won more awards and commendations than any other chronograph. Zenith set another record in 2017 with the debut of the Defy El Primero 21 chronograph, which can clock elapsed intervals not merely to the nearest 1/10th, but to the nearest 1/100th of a second. This mechanical feat is made possible by El Primero 9004, in which the stopwatch function has its own movement with a separate escapement that oscillates at a frequency of 360,000 vibrations per hour (50 Hz).

Although the original Caliber 11 is no longer manufactured, the brands that participated in its development are still justifiably proud of their innovation. TAG Heuer’s Product Director Guy Bove said, “TAG Heuer has presented numerous precise timepieces during the past 150 years, but probably none of them has left as an indelible a mark on watchmaking as the Chrono-Matic.” The Monaco, which once encased Caliber 11, soaked up some limelight in 2019, its 50th anniversary year. A different limited-edition Monaco was unveiled at each of several commemorative events in Europe, the United States and Asia. The historical and technical highlights of this icon are chronicled in the book Paradoxical Superstar, published in May 2019.

Seiko’s Chairman and CEO Shoji Hattori says that the launch of the automatic chronograph movement was part of the success story that led “to the development 30 years later of Spring-Drive technology, which plays a central role in the launch of new versions of the Grand Seiko in 2019.”

The Winner

Now let’s return to the conundrum of who, in fact, developed the first automatic chronograph. Which brand stands on which step of the winners’ podium cannot be answered unequivocally from today’s vantage point. What is certain is that each brand achieved a success of its own. While the first prototype of El Primero was introduced at the beginning of 1969, Breitling, Hamilton and Heuer didn’t unveil their development until three months later, but they were able to present the largest number of functioning prototypes at the Mustermesse in Basel. And Seiko premiered its first self-winding chronograph wristwatches in May of the same historic year. How it was possible for several manufacturers to present the most important watch innovation of the postwar era all in the same year remains puzzling even today. From a purely horological perspective, El Primero has been “Number One” for 50 years: “It set standards not only in technical terms, but it was also a feast for the eyes, almost poetic in its beauty,” said Gerd-Rüdiger Lang.

This article was originally presented in the August 2019 issue of WatchTime.

in the 6th paragraph it is stated that the chronoswiss was founded later than 1969. it was around since decades before that, and is not a brand associated with automatic chroographs, if they ever had any.

the 1/8 second time division of still contemporary highend chronographs is an utter joke, and really demonstrates the toy nature of these gadgets. 1/10 and 1/5 divisions are respectable but definitely not 1/8.

that said i enjoy these toys; own chronograps of all three divisions, and use with satisfaction.

How can Zenith be first when there is proof that there is Seiko 6139 watches dated to february 1969? Announscing a watch and bring to market is 2 very different things

We are the winner – not only with participating in the advancement of mechanical watches in general, but in seeing complications which used to be exorbitantly priced becoming relatively common, enough the common man can afford one. What has happened to the watch industry of late, however, is a shadow of it’s former self. Watches were something that adults achieved thru work and accomplishment – you rewarded yourself with buying a timepiece commensurate with your accomplishment in life. Now it’s a market churning style and flipping watches that their fathers would have been satisfied wearing for 25 years and passing down. Swiss makers are churning out watches in the millions a year now – and for all that, quartz, that revolutionary engine that Rolex tamed for sports timing, is now the heart of watchmaking. Add solar charging, and power reserves of months, not days are possible, Add a micro chip to power a stepper and voila, not only perpetual calendar is possible, but also power saving, which reawakens the watch after powering down the dial and then adjusting to the correct time – months later.

It was a Quartz revolution, accurate timekeeping to seconds a year vs 40 seconds off a week for a certified chronometer is now taken for granted. That doesn’t mean the luxury watch market has diminished, tho – those watches sell precisely because they still express status and accomplishment – while those who really need the expression of time in a complication can get it at a reasonable cost. Because of all those flippers – a solar quartz perpetual calendar is commonly sold on auction sites for less that 100USD. And those “clever” Japanese supply most of that market, Who might be even more clever, tho are their suppliers, the Chinese, who supply many of the components the Swiss buy, too. And they are now competitively taking not only business away from the Japanese, they can also put the squeeze on Switzerland by throttling exports of their parts.

We are facing the day of the Chinitzerland watch becoming exposed for it’s content. What was simply a strategic goal of a collaborative effort in the 1960’s has now been overshadowed by global sourcing and political protectionism of a national industry.

Interesting times.

It was Quartz Revolution, not a “uartz Crisis”. Seiko was able to introduce the first automatic chronograph and the first Quartz watch in the same year. That’s quite an achievement….

Enjoyed the article

History in watch making. The first chronograph automatic, and the movement.

Who is the first? Let’s say it in chess terms, remise.

The odd way of the project 99 club, to put the crown at the left side made that watches one of a kind. I have much admiration for Heuer, but overall i like Zenith watches more. Especially the Defy models which have that twist of dolce vita, and being there for technology enthusiasts.

Next that Zenith made great models, they are in the reach of a lot of watch enthusiasts. Sure, Tag Heuer is also reachable for manny watch enthusiasts. Both have a great history, so which brand you pick up, the watch would be a good buy.

Breitling, Hamilton, Seiko, all made durable watches which satisfy ownership.

The words, there are no bad watches anymore, is almost reality.

The remake of icon pieces is nowadays watch paradise. Modern and hightech production methods which make mechanical movements very reliable, accurate, and sustainable.

Complex complications become more and more reachable for every watch lover.

See how silicon, silicium springs finds it’s way to affordable watches, it is a matter of time you can go for a reasonable priced tourbillon under 12K.

Apparently this was a 4 hourse race, with Omega/Lemania working on Cal 1340 if I am correct. It was completed in 1970? A movement which differed significantly from the 1969 releases.

The penultimate paragraph states:

Seiko’s Chairman and CEO Shoji Hattori says that the launch of the automatic chronograph movement was part of the success story that led “to the development 30 years later of Spring-Drive technology, which plays a central role in the launch of new versions of the Grand Seiko in 2019.”

I think Seiko’s current Chairman and CEO is Mr. Shinji Hattori, not Shoji.

Great article and good summary of the contributions of each group. I own a Seiko 6139 from Feb 1969 and have seen pictures of one from Jan 1969, but who knows when those were actually sold. I’d love to have examples of the others. And like you said Zenith is probably the “winner” long term since they have had so much success.