Sometimes, the analysis of which watch to buy proceeds little further than, “Wow, that one looks cool.” Chronographs, however, are often thought of as “tool watches,” and when it comes to tools, you want the right one for the job. To guide your choice we’re revisiting this guide from the WatchTime Archives, offering 10 factors to consider when selecting a chronograph to help make sure it suits your wants and your needs.

1. It’s the Way That You Use It

Salesman: “How will you use your chronograph?” Customer: “Use it? I hadn’t thought about that.” Chronographs are not just for timing races – they offer many practical uses. Tracking cooking times, parking meters, walks or runs, bike rides, exercise routines, meetings, and guaranteed pizza delivery are often cited. So is determining the shortest commuting route. With your chronograph, you can find out how long an “instant” oil change really takes. Or, try this: when they tell you your table will be ready in five minutes, press the start button. When your wife says she will be ready in five minutes, press the… no, wait, that’s a bad idea.

Lawyers and others who sell units of time can track billable hours. Or you can pass the time by measuring intervals spent stuck in traffic, watching TV commercials, or waiting for the doctor/dentist. Activate your chronograph for a short time when you have an idea you want to remember. Later, when you see the odd elapsed time, it will jog your memory (assuming the idea is still in there). Other uses require that the watch have particular features. For example, most chronographs can’t be operated under water, and many can’t time hours-long events. Some chronographs are designed to run continuously, while others are not (more on this later). Choose carefully if these are features you desire.

2. Can You See Me Now?

Legibility – the easy-to-read display of elapsed times – can no longer be taken for granted. In days gone by, manufacturers assumed that chronographs would be used and relied upon, so legible elapsed times were a given. Today, elapsed-time indications are often sacrificed on the altar of fashion. Manufacturers will ditch them in a second for the sake of a design they think will induce the customer to say, “That one looks really cool,” and reach for his or her wallet

But you’ll want displays that are easy to make out when you’re using your chronograph, so pay attention to the dial, and especially to what’s missing. If you need to read the chronograph in the dark (we won’t ask what you might be timing), you’ll have to search even more diligently, as very few chronographs will suit your needs.

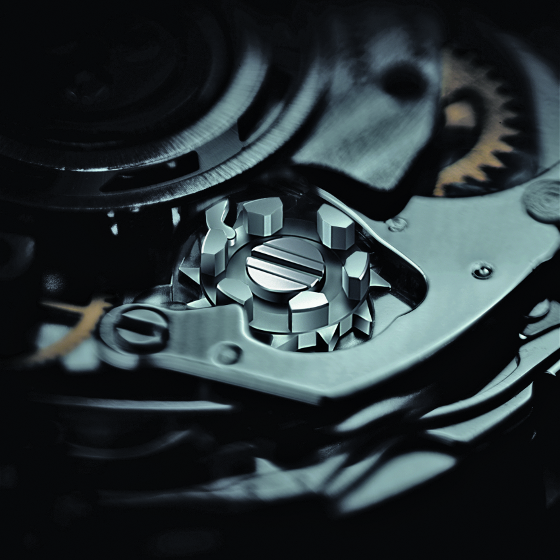

3. The Origin of the Species

Chronograph movements come in a range of flavors: in-house, third-party and hybrid, integrated and modular, and more. To some, this is a virtual caste system, and place of birth and physical form confer status, or stigma, for life.

In-house chronographs are typically integrated, not modular, in design, and a column wheel usually occupies central command (more on these concepts below). In-house movements can offer fine functional finishing, careful adjustment, and the resulting smooth feel of quality. They can also be beautiful to behold. In-house production gives brands the freedom to produce singular designs, and offers control over every step in the manufacturing process. Of course, all of that requires investment. Chronographs with in-house movements tend to be rather dear, and service can be costly as well. The service is also likely to take a long time, and be performed far away. Collectors often joke about the number of frequent flier miles their timepieces have accumulated. That’s called using humor to mask pain.

Third-party movements offer their own advantages. Most have been around for awhile, or they are based on tried-and-true designs, so they are extremely reliable. Service is relatively inexpensive and can usually be handled without sending your watch overseas. Replacement parts are in ready supply. These movements are generally quite sturdy, and they can be excellent timekeepers. (ETA offers mechanical movements in various grades, and as you move up the quality ladder, the timekeeping improves. The top level is COSC-certified.) On the other hand, third-party movements are produced in large quantities, so they are not exclusive. They exhibit little or no hand work. Their components are often stamped, not milled.

They are rarely beautiful to behold. They tend to employ mechanisms designed primarily to reduce costs. Some of these calibers can be found in watches costing from hundreds of dollars to several thousand, even reaching into five figures, which can be distressing to those who buy in at the upper end of the spectrum.

4. Built-Ins and Add-Ons

When it comes to chronograph movement design, purists prefer integrated to modular, because the integrated variety is designed to be a chronograph from the ground up. That means all components are optimized for that use. That can be important because a chronograph can be a “heavy” complication that requires significant power to operate. If engaging the chronograph generates a drag the base caliber was not designed to handle, that can affect timekeeping, which means the chronograph can’t measure elapsed time accurately (though most of us would never notice the split-second error). Modular movements, also called sandwich or piggyback designs, begin with a base caliber and add a chronograph mechanism mounted on a separate plate, usually on the dial side. If you want a nice view of the chronograph through the display back, an integrated movement is the way to go.

Some feel that in all but the finest executions, a modular construction will be less precise. The chronograph seconds hand may jump or stutter when started, the continuous seconds or the minutes hand may jump slightly when the chronograph is activated (even the date disk may move slightly), and the feel of the push-piece is not as smooth and buttery. As noted above, modular designs can also generate more amplitude-reducing drag when the chronograph is engaged. In two recent WatchTime tests, a modular chronograph’s amplitude dropped by 73.5 degrees on average when the chronograph was switched on, while an integrated model’s fell by 19.5 degrees. (The integrated model also used a vertical clutch – see below.) If you’re not sure which type of movement a given watch contains, there are some modular tip-offs. They include a high jewel count, no chronograph components visible through the display back, a date display that sits down in a hole and not directly below the dial, and a crown that is not on the same horizontal plane as the chronograph buttons (though some brands try to disguise this with oversized crowns, push-pieces, and guards).

5. Make It So

Imagine what would happen if you could activate the reset mechanism while the chronograph was running. The phrase “train wreck” comes to mind, and yes, the pun is intended. (Note to newbies: see “train” in Berner’s.) To prevent this and other disasters, chronographs employ systems to coordinate actions initiated by the push-pieces. As you might expect, there are different systems, and each has its supporters and detractors. The traditional system, favored by purists, is the column wheel, so named because the key component looks like a wheel lying on its side with a series of small, vertical columns rising up from it. Each push of a button causes the wheel to turn, and as it turns, the columns, and the spaces in between, move in small increments. This action moves the ends of levers that rest against the column wheel, and the levers control the chronograph’s start, stop and reset functions. Column wheels are traditional, expensive to manufacture and to adjust, and difficult to service. They also look great, and they provide very smooth push-piece feel. In other words, they’re made to order for luxury chronographs.

Column wheels were once ubiquitous, but some manufacturers searching for efficiencies developed cam mechanisms to take the column wheel’s place. The new system functions much like the traditional one, with an eccentric cam (a thin piece of metal with an irregular shape) replacing the column wheel. Cam systems are generally less expensive to manufacture, easier to adjust, easier to service, and not as nice looking. In use, cams generally perform as well as column wheels. NASA certified both the column-wheel and cam versions of the Omega Speedmaster for space flight. Chronographs powered by the Lemania Caliber 5100, with cam switching, were certified by several countries for military use. When the Swatch Group announced that it would halt Caliber 5100 production, watch manufacturers using the movement objected, saying it was the only caliber that could withstand large shocks without the chronograph seconds hand stopping. (The 5100 was eventually discontinued and replaced by an ETA caliber.) Finally, the ETA 7750, which is also known for being rugged, uses cam switching. If you’re looking for a tough tool watch and you don’t care about movement aesthetics, cam switching will fit the bill. If you care about tradition, a nice view through the display back, and the approval of purists, the column wheel is for you.

6. Let’s Get Engaged

The column wheel and cam issue orders, but other components further downstream transmit the mainspring’s energy to the stopwatch, and once again, there are competing systems. The traditional system uses horizontal or lateral coupling to transmit energy. When the start button is depressed, a wheel mounted on a moveable bridge or lever slides horizontally to link the fourth wheel, which rotates once per minute, with the chronograph center wheel, which drives the chronograph seconds hand. The intermediate sliding wheel is required because if the fourth wheel meshed directly with the chronograph center wheel, the chronograph wheel (and the seconds hand it activates) would run counterclockwise.

The horizontal meshing system is aesthetically pleasing because it enables the owner to watch the chronograph engaging and disengaging. However, meshing teeth can cause the chronograph seconds hand to jump when it starts, and because the teeth used for chronograph coupling have a different shape, or profile, than teeth used for continuous power transmission, regular or continuous chronograph use can cause the teeth to wear. The extra wheels in this system can also sap the mainspring’s energy, affecting the balance wheel’s amplitude, and so, timekeeping. The other main contender in this arena is known as the vertical clutch. Though not as aesthetically pleasing (because the chronograph engagement takes place largely out of sight), this system offers some advantages. It reduces chronograph drag, the chronograph seconds hand does not jump when started, and the chronograph can run continuously without causing excessive wear.

In simple terms, in the vertical system, the chronograph is always “in mesh” with the timekeeping wheel train, and a clutch engages and disengages the chronograph. The clutch means smooth starts for the chronograph seconds hand, and the “always in mesh” feature means that starting the chronograph does not generate significant additional drag. The drawbacks include cost, poor aesthetics, and the fact that the vertical clutch can be difficult to service. If you’re a traditionalist who will happily trade a bit of precision for the joy of watching your chronograph in action, the horizontal coupling system is for you. If you’re more concerned with precise starts and stops, or if you like to leave your chronograph running all the time, consider the vertical clutch variety.

7. The Need for Speed

There is a direct relationship between a movement’s frequency and the size of the fractions of a second it can measure. The higher the frequency, the smaller the fractions. So, as the average frequencies for wristwatch movements have increased over the years, chronographs based on those movements have become able to measure smaller and smaller fractions of seconds. Movement frequencies are often expressed in vibrations per hour, or vph. This relates to the speed of the balance wheel’s oscillations. Viewed from above, the balance wheel swings back and forth, left and right. Each swing to the left or to the right is a vibration. Each vibration, or beat, causes the seconds hand to make one jump forward.

The most common frequency for modern mechanical movements is 28,800 vph. To calculate how many vibrations that is per second, divide that rate by 3,600, which is the number of seconds in an hour (remember that vph is vibrations per hour). The answer is eight, which means that the movement is capable of measuring time to 1/8 of a second. Similarly, a watch with a frequency of 18,000 vph can time events to the nearest 1/5 of a second. A frequency of 21,600 vph yields accuracy of 1/6 of a second. A watch with a frequency of 36,000 vph can time events to the nearest 1/10 of a second. If the fellows making 1 Hz, or 7,200 vph, movements (they include the companies Grönefeld and Antoine Martin) ever decide to produce a chronograph, it will measure only half-seconds. Having mastered this bit of math, it is important to keep in mind that the movement frequency does not always translate directly to the motion of the chronograph seconds hand. That’s because the manufacturer can use gear ratios to change the rate at which the chronograph seconds hand moves around the dial. A chronograph with a 28,800-vph movement might be (and often is) geared to actually measure 1/5-second increments on the dial, not 1/8-second.

In recent years, some manufacturers, notably TAG Heuer, have started producing chronographs with two mainspring barrels, two wheel trains, and two escapements that run at different frequencies. The timekeeping escapement can tick along at a leisurely frequency meant for movements that run for years on end (offering low wear and a long power reserve), while the chronograph escapement can operate at a much faster frequency that allows it to measure hundredths or thousandths of a second and beyond. That faster speed means the chronograph’s mainspring unwinds quickly, so super-fast chronographs typically cannot time multi-hour events. For example, TAG Heuer’s Mikrograph, which measures to the nearest 1/100-second, can time events only up to 90 minutes in duration. If you need a chronograph that can measure specific intervals, such as 1/10s of a second, pay attention to both the movement frequency and the chronograph seconds track on the dial to make sure they meet your needs.

8. Exotic Extras

Anything one watchmaker can invent, another can make more complicated, which leads us to some exotic forms of the chronograph: the flyback and the rattrapante. The flyback, sometimes called the split-seconds flyback, can be used as a traditional chronograph, but a special feature allows the user to stop, reset, and restart the chronograph with a single push of a button, usually the one at 4 o’clock. The flyback’s drawback is that the reset mechanism makes it difficult to get a precise elapsed-time reading. When you depress the 4 o’clock push-piece, the chronograph seconds hand does not pause for you to take a reading – it instantly flies back to zero. If you’re looking at a finish line to judge when to push the button, you can’t also be looking at the watch to get the elapsed time. The flyback is much more useful when measuring fractions of a second is not required. For example, if a pilot has to execute a series of turns at specified time intervals, he can quickly reset and restart the chronograph before making each turn. Another exotic option is the rattrapante chronograph, also known as the split-seconds or doppelchronograph. Rattrapante means “catch up” or “catch again” in French, and doppelchronograph means “double chronograph” in German.

These watches have two chronograph seconds hands, one on top of the other. One, the rattrapante hand, can be operated independently of the other by means of a third push-piece, usually located at 8 or 10 o’clock. The extra seconds hand allows the timing of a second event, or splits within a single event, though with one significant limitation we will discuss momentarily. For example, in a 100-yard dash, you can start the chronograph, push the button at 8 or 10 o’clock when the first runner crosses the finish line, and the button at 2 o’clock when another runner crosses the finish line. The two chronograph seconds hands will show the two runners’ times. Pushing the rattrapante button again causes the rattrapante hand to catch up to the primary chronograph seconds hand, which is how you time splits in a longer race. For example, in a one-mile race, you might press the rattrapante button each time the runner passes a quarter-mile marker, reading the time for that split. After reading the time, you can press the rattrapante button again to reunite the chronograph seconds hands, until the next quarter-mile marker comes up. The limitation is that the rattrapante hand has no minutes counter of its own. So, you can time two events, or splits within a longer event, as long as the rattrapante hand does not have to measure more than one minute.

To overcome this limitation, you can purchase an inexpensive quartz stopwatch, or one of the most sophisticated (and, at $120,100, one of the most expensive) chronographs ever produced – the Lange Double Split, which offers a double rattrapante function – each chronograph seconds hand has its own counter on the 30-minute totalizer. The four chronograph hands (two seconds and two minutes) also have flyback functionality. And, the movement has two column wheels – one for stop-start-reset, and one for the rattrapante functions. Now that’s exotic.

9. Do You Need a Date?

It’s a hard fact of life that some of the best looking and most popular modern chronographs, and many classic vintage models, do not have a date. Think Rolex Daytona, Omega Speedy Pro, IWC Portuguese, and vintage chronographs from Rolex, Patek Philippe, Breitling, and many others. Some of us want a date display, but the chronograph that has captured our hearts does not have one. That leaves the cellphone option, which, in our view, is acceptable, even for a true watch aficionado. As long as you’re wearing a watch, what you do with your phone is your business.

If you want to find out if you can live without a date display on your wrist, take a daily-wear watch and change the date so it’s wrong. Or, put a tiny bit of tape on the crystal to block the date. If after a week you have not experienced withdrawal, you’re ready for that chronograph sans date.

10. But Wait, There’s More

Adding a scale to a chronograph dial or bezel expands the range of information the timepiece can convey. Think of these scales as primitive apps that increase the chronograph’s usefulness.

One set of scales is based on the relationships between time, speed, and distance – if you know two values, you can calculate the third, and the scale makes the calculation for you. For example, a tachymeter allows you to calculate speed over a known distance, typically kilometers or miles. Most tachymeter scales start at 400, located at about eight seconds on the dial, and end at 60, at 60 seconds, or 12 o’clock. A simple example of tachymeter use involves determining the speed of a car, where time and distance are known. Start the chronograph when the car passes a mile or kilometer marker, and stop the chronograph when the car passes the next marker. Look at where the chronograph seconds hand points on the tachymeter scale, and that number represents the car’s speed.

The tachymeter can only measure for one minute, and it is typically graduated to show only a certain range of speeds (for example, between 60 and 400 kilometers per hour). The speeds of runners (too slow) and supersonic jets (too fast) fall outside the tachymeter’s range.

A telemeter allows the user to calculate distance based on known speed and time. The scale is graduated using the speed of sound through the atmosphere. The scale allows the user to determine the distance to an event that can be both seen and heard. The two most widely cited examples are lightning and artillery fire. The user starts the chronograph upon seeing the flash of light and stops the chronograph when he hears the sound. The approximate distance to the event can then be read off the scale. Miles and kilometers are the most common units of distance.

Pulsometers and asthmometers work on the same principle to indicate a patient’s pulse or respiration rate, respectively. The scale is typically explained on the dial. For example, it may read “Gradué pour 30 pulsations” or “Graduated for 5 respirations.” The user starts the chronograph and stops it when the indicated number of heartbeats or breaths has been counted. The seconds hand will point to the number of beats or breaths per minute on the scale.

With that, we’ve reached the end. Thoreau said, “Time is but the stream I go a-fishing in.” We hope this little overview helps you catch the fish that is right for you.

This article first appeared in WatchTime’s February 2014 issue.

Good article. I learned from it.

One thing you should know: Why does anyone need a chronograph?

Good article..helpful.. why did you not mention Vacheron and Patek (the top two quality brands along with AP)..?

thanks for sharing such an informative post

Love chronograph. Love watching hour second minute hand. Watch during holiday. Changes i want one dial with time showing our country and another visited country

This blog is great, the best chronographs in my opinion are Rolex Daytona, Tag Heuer Carrera, Breitling Aviation Chronograph, OMEGA Speedmaster, Zenith El Primero.

I have a Sinn EZM10 which I like for a variety of reasons.

Very good article. Gave in-depth information. Very useful. Thank you.

Thanks for comprehensive explanation. I have two chronograph watch. One has 12, 30 and 60. The other has 60, 60 and 24. Whats the difference? Thks

Fascinating read: thank you for such an informative article.

Good article. But reinforced my believe that while I strongly prefer mechanical watches to quartz, chronographs are the only category where I prefer to buy quartz.

Interesting point, I hand not considered. Is that because of accuracy or reliability?

Liked the article. But still came away thinking even more strongly that while I much prefer mechanical watches to quartz, chronographs are only area that I’d rather buy the quartz.

Very helpful.

Thank you.

Fantastic article I learned a lot

Enjoyed reading your detailed Chronograph description. I may buy a Tissot Sport. Not so much because it’s a Chronograph, but it looks great and for the price is Swiss Made.

What say you? Darryll V.

My husband fours drawing for client so I was wondering which would be the best watch to buy that could help him to keep count of the time he has spent on his work

I read this article at least three times when I first encountered it about 12 months ago. It was extremely useful. I ended up purchasing a Oris Valtteri Bottas limited edition and have been thrilled with it. My other front runners all had bigger names and bigger price tags. But they also had some less desirable features. I wanted at least a 44mm dia. dial and readability was key. Other considerations I took into account only after reading this article, ended up making a substantive difference. Thanks again for re-publishing this. I recommend it heartily.

Wow.. this is hands one of the most concise, precise and incredibly useful rundowns on this aspect of timekeeping… BRAVO sir! I’m bookmarking this so I can scan over different areas when curiosity arises. Thank you for taking the time to write this out!

Very informative,even as a refresher for the experienced. Enjoyed the lighthearted bits as well!

I am currently in the market for a new watch and this article is the best I have found thank you.

My Breitling Aerospace that I have worn for 29 years is needing to be replaced and they thing that amazes me is how large so many watches are now. Since I do fly for a living in very modern jets even now on a non-precision approach a good chronograph can’t be beat right where my time needs to be on my wrist.

Thanks again for such a well written article.

I found this very informative about what I had not been told about before. Thank you.

I have an Omega Speedmaster.

I don’t understand all the hype about chrono accuracy to 1/8 or even 1/100 of a second. The timing function and biggest source of inaccuracy is the user reaction time to start and stop. A function can be no more accurate than its least accurate component. This seems to be ignored when manufacturers tout how accurately their watch can time an event

Precisely! Excellent point. And with the ubiquity of smart phones with built-in digital timers + stopwatches, the value of a chronograph decreases. The hype IMHO is more remnant of yester-years when it had actual functional value coupled with the precision accomplished with mechanical gears.

Excellent article.

Still the best way to get a beautiful panda dial.

I have a Sinn EZM10. I use it from time to time for its intended purpose; mostly I just like looking at it.

I like buying Pre-owned vintage watches and mmy customers give me best motivation ever

You can’t overstate the importance of the dial. After a lot of looking for a truly rugged chronograph dive watch, I found one I really liked, bought it, Then discovered that those big super luminova covered hands that made the watch so easy to read in the dark, blocked visibility of the sub-dials–it takes the minute hand an excruciatingly long time to get past the hour and minute sub-dials. Nice thin tritium-lit hour and minute hands would make this watch perfect.

The older I get, the simpler I like my watches. At this point I prefer a good old 3,hand automatic. However, I still love my Breitling Navitimer Montbrillant Datora, even though it isn’t exactly the easiest watch to read. It has the day, date, even the month and of course a chronograph function. It is just very cool.

I have a Smartphone, actually two, one of each flavor, Apple and Android. Both have the ability to give very precise answers to the “Do you have the time question?” I use the chronograph function to time my cigar moments. I have not, nor will I ever pull out my phone when asked what time it is. I pull back my cuff and glance at my wrist. Smartphones are precise but a wristwatch is elegant. Elegance trumps precision

Love your assessment. I only own one chronometer, a Speedmaster, the rest of my small collection are dress watches that exude elegance. Vintage Constellation, vintage Deville, new JLC, etc. I love elegant watches, which is why I’m not fond of Rolex.

Truthfully, you probably buy a chronograph because you think it is cool. Most people will not use it as a tool. Your cell phone will do a much better job as a tool than a chronograph. Buy a chronograph because you love the way it looks and because you appreciate the work that went into creating it. But remember, repairing it if it stops working will probably be a long and expensive proposition, especially if it has an in house movement.

An in-house column wheel flyback chronograph with a vertical clutch can be very expensive. Or you can spend $200 on a vintage Citizen Bullhead chronograph. :)

A vintage Seiko 6138 chronograph from the 70’s had all the features of the most expensive watches of today, and for a lot less money. The cool factor isn’t appreciated by many but it’s there if you can get beyone it not being Swiss made.

I love chronographs and have a ‘couple’ – Omega Speedmaster Snoopy Award 2003 (bought with funds left to me when my father-in-law passed away), Hanhart Pioneer Tachytele (mother bought me it before she went blind) – why did I make these choices? am interested in spaceflight especially the Apollo missions to the moon and am also interested in WW2 Luftwaffe and German Secret Weapons. But All chronographs are great in my eyes and to wear one is a nice feeling… Great article and great photos as always.

This is a very informative article for those, like myself, who are interested in how a mechanical watch functions.

I found the comments on modularity to be especially interesting as I would buy a mechanical chronograph for it’s timing accuracy.

While I agree that the phones we carry – actually a small computer- would be able to provide better accuracy than a mechanical chronograph, battery powered devices seem to have a way of being discharged just when most needed.

I especially agree about the comment that legible ( elapsed timing ) functions are being sacrificed on the altar of fashion. I am currently in the market for a chronograph and have found far too many displays are nearly unusable due to the design of the face and hands.

Regarding night time legibility:

When the pupils of my eyes are dilated due dim light, I prefer to glance at a watch rather than the blinding light of a cell phone display.

Thank you for this unusual piece summarizing what I should know when buying a watch with a complex dial… This article fills in a lot information on how we can properly make use of the different functions.

There’s also a watch made in Japan, the Casio Edifice Pilot’s Edition EF-527L which is pretty and has a Slide Rule on the outermost dial face operated by an 8-o’clock crown!…

But of course you might not feature Casio in this summary.

I appreciate the work put into this article, what makes this newsletter Special.

Thanks again!

M. da Silva

I had a Casio Edifice which I loved, but in actual use there was so much packed into it, and some of the positions were marked with such tiny letters that to do anything more than read the time I had to put my reading glasses on – which kind of spoilt it. I gave it away in the end…

I think of chronographs as the entry complication for guys who are not interested in moon-phases (now there’s a beautiful but fairly useless complication.)

While I agree that electronic alternatives have rendered chronographs obsolete, I would argue that as long as you have a phone with you, you probably don’t need to wear a watch either. I wear a watch because I feel undressed without one and I love the way a chronograph looks.

Just as it is more convenient to glance at your wrist to tell the time than it is to take a phone out of your pocket, so it is more convenient to have the chronograph on your wrist when timing something.

I run training classes and I use my watches to time tea and lunch breaks, as well as time assessments for competency certifications. I have three mechanical chronographs and two analogue quartz chronographs and I wear them all to class, just not all on the same day!

I like this article with exception to note 7. author did not give credit to the movement of this company. It looks like GP or Girard Perregaux movement. Yet you acknowledge crappy company like Tag. Is there a promotion of pushing certain companies through media? I think Tag more inline with Oris, Tissot, Invica, Fossil, Citizen, Hamilton, Nomos. And, not with league as GP, JLC, UN, Lange, Rolex, Cartier, Glasshutte Original, AP, FP J, and Gruebel Forsey.

I find it upsetting that you would lump Invicta or Fossil with a brand such as Nomos, You also underestimate Tag Heuer whom have just given us a tourbillon and the mechanical 1/100 chronograph function.

Excellent piece. Very informative. Great writing style too!

Great article, but why does a pop-up ad for the TV show Bar Rescue appear on every page? Very annoying.

This was an error on the server of our advertising agency, has been fixed. Sorry.

Thanks for the interesting article.

I love chronographs and have owned two … still have one … but I have never known anyone except an old-time physician to ever use its timing features. Like so-called Pilots watches … which are not necessary because all aircraft today have clocks. I love their appearance but would have no use for one, even an IWC “Spitfire” which I think in appearance is the cat’s pajamas in pilots watches. And truth be known I think most people buy chronographs for show and not because they need their features.

As for timing, etc., the cheapest hand-held smart phones have timers that are more accurate than any mechanical chronograph and probably most quartz watches, too, so why would anyone really interesting in timing of speed, pulsations, etc. want to fiddle with a watch that is only reasonably accurate … assuming that close timing is even necessary.

I am not opposed to watches that offer conveniences such as the Rolex Day-Date I have worn for about 30 years now. I bought it when I was doing a lot of international travel and I would awaken in some strange city and it was nice to know the day (I always knew the city.). And, truth be known, I bought it because at the time bling was pretty important in my business and I thought it was blingingly beautiful. For the record, I don’t travel overseas much anymore but I still love the watch.

Very informative, thanks for posting!